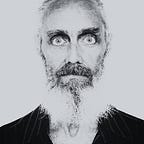

Death of Naivety

When I was 14 or 15 years old I killed a bird.

As a child I didn’t consider myself violent. Nor would anyone else have, I believe. I didn’t get into fights with other children; rather I resisted engaging in scenes of violence, either by running away or absorbing the blows without retaliation.

I grew up with family pets (rabbit, dogs, cats, ducks, chickens, fish) whom I played with, lavished affection upon and observed with curiosity. I loved them.

So why did I not cherish creatures that weren’t considered pets; those that lived wild and free, animating the large garden of our family home, or the local countryside?

Killing Games

During the school summer holidays I would skip around our garden, swatting bumble bees, wasps, bluebottles, etc with a tennis racket, gleefully immersed in my acrobatic slaying. It was just a game to me, and in an instant, at the call of my mother, I would cast aside the improvised weapon, forget my bout of frivolous violence, and run inside for lunch, to replenish my energy with a ham sandwich, glass of cherryade and a banana.

One springtime, perhaps when I was 9 or 10 years old, I was playing on some waste ground next to the local rec (recreation ground) with some other boys. One of them caught a frog, shoved a straw up its anus and blew it up until it exploded. I was horrified by the casual cruelty of the act, though I tried not to show my shock. I remember the boy’s nonchalant laughter decorating the aftermath of his heartless deed, and the nervous mirth expressed in response by the other boys present. Instantly I felt distrustful of and repulsed by him, unsettled by what I had just witnessed.

Outer Exploration of Inner Boundaries

Some years later my father bought an air rifle. I don’t know why, as I don’t ever remember him using it beyond showing me how it worked. From the age of about 14, with his permission, I would occasionally take the gun to the local countryside with my friends. We would fire at old tin cans lined up along the top of a fence, or even at birds in flight, though we never hit one.

I remember once a friend came around to my house and we set up in the bathroom with the air rifle when my parents had gone out, having a prime panoramic view from the first floor window, over the back garden, the field beyond, and the garden next door. We were careful not to be seen, keeping the gun barrel within the confines of the window frame, and I was aware that we shouldn’t shoot upwards in case the pellets travelled far enough to hit someone unseen at a distance.

Our aim was to practice shooting targets in the garden; plants, fence posts, etc. I noticed in the garden next door that there were fruits or vegetables planted under long, low polythene tunnels. It was wicked of me, but I shot pellets through the polythene, knowing that the hot air accumulated within the tunnels would escape, and later the cold air of night would descend through the holes I’d made, over time potentially ruining the crops. (The gardener, whose crops they were, noticed the holes, apparently found some of the pellets, deduced the source and complained to my father, who chastised me accordingly.)

That day we unwittingly tested our moral comprehension, when my friend, despite my protestations, couldn’t resist shooting at a horse that had wandered into view behind the two-metre-high wall, in the neighbour’s field beyond the end of the garden. The placid animal was standing broadside to us, and his shot hit the top of its left thigh. The horse’s leg twitched involuntarily with the impact of the lead pellet, but the creature remained unmoved. Immediately I felt agitated by a strong sense of wrongdoing, and concluded our shoot forthwith.

Naivety Forfeit

I discovered my threshold one cold winter’s day. I was bored at home. It was a Saturday morning and my parents were out. I took the air rifle out to the back garden, seeking targets. I thought about birds. I’d never shot one, never being accurate enough with the rifle to hit one in flight.

As I approached the garden, across the yard, I heard a bright voice, chirruping ahead of me. It was coming from within the thick prickly throng of the old Holly tree. I stealthily approached it, slowly cocking the gun. I peered into the darkness of the deep ancient Holly in the dimness of the overcast morning, and after a short while saw something move. My eyes gradually adjusted to the blackness as I gazed into the abyss, and fixed upon the small plump silhouette of a sparrow; its head cocking side-to-side, listening intently for replies to its morning calls. It seemed to be either unconcerned by my presence, or oblivious to any impending threat I might be posing.

Silently I raised the barrel, aimed and shot, just a metre away from the creature. It never stood a chance.

The Dawn of Awareness

The bird instantly dropped limply through the thicket of dried debris that had accumulated around the inner core of the tree branches. It disappeared from sight with a couple of soft thuds, into the darkness below.

I had ended its life.

Suddenly I felt empty, as though something vital had been removed from my being.

I felt an unfamiliar and uncomfortable mixture of emotions creep over me. Horror, disgust, shame, all bundled into one crushing, prolonged moment of inescapable guilt.

And more than that, I felt an unparalelled desperation of knowing that I could never revoke this act of betrayal. For betrayal it was. Simply by us being present together, sharing our realities, there existed a tacit trust. I had breached this trust; ended its life, thoughtlessly, pointlessly.

Responsibility and Beyond

Now, almost four decades later, I carry a matured complex of that emotional experience. My initial feelings of horror, disgust, shame and guilt have decocted into a seam of reflective sadness, acceptance and self-forgiveness.

I’ve developed an elevated awareness of the responsibility I bear when entrusted with the life of another, whether there exists a pre-acknowledged trust or not.

Others, whether they be plants, animals, humans or even mineral structures, are aspects of our personal and communal environment. And when we, with intention, negatively impact their existence by our actions, then we also reduce the quality of our own lives, as the conditions of those impacted are reflected back to us in their degraded or annihilated states.

I am grateful for that which I have learned through my fateful encounter with that small bird. My ignorance was forever removed. And more than that, I have realised that our environment is not simply an objective reality, existing beyond the sphere of our personal influence, but is conceived through and maintained by the expressions of our every action.